A Special Feature to mark Jubilee 400

The Yorkshire Society, which honours the achievements of distinguished people born in Yorkshire by erecting Yorkshire Rose Plaques in their name, usually celebrates famous Yorkshire men. In March 2007 the Society came to the Bar Convent, York, to set up a plaque for Mary Ward, the first woman to be so honoured. January 2009 marks another celebration of her extraordinary life and achievements as the sisters of the Congregation of Jesus and the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary mark the 400th jubilee of their foundation. Mary Ward’s is a unique story of courage, determination and a remarkable vision of women’s role in church and society centuries before its time.

Born in 1585 Mary lived during a period of severe persecution against recusants, Catholics who refused to attend the state church. She was one year old when her fellow Yorkshire woman, butcher’s wife St. Margaret Clitherow, was pressed to death in York for harbouring priests. Margaret belonged to a network of recusant women, under the supervision of doctor’s wife Dorothy Vavasour, who ran a maternity clinic under cover of which they could baptise babies and maintain their threatened faith. She and Mary Ward shared the same spiritual director, Father John Mush. The women in Mary’s family also belonged to underground networks. Her maternal great-grandfather, Sir William Mallory of Studley Royal, near Fountains Abbey, had stood for two days with drawn sword outside his parish church ‘to defend that none should come in to abolish religion’. Her grandmother, Ursula Wright of Ploughland Hall in Holderness, spent fifteen years in prison for her faith and her aunt, Grace Babthorpe of Osgodby, spent the first five years of her married life in prison. It was often safer for women to remain Catholic while men conformed in order to save the family fortune and home from the savage fines imposed on recusants. There were no bishops in England at this time and the whole system of church and sacramental worship had collapsed. It was kept going in secret, often in the households of landowners able to hide visiting priests within the home, disguised as servants or tutors. Many of these were Jesuits, like martyrs Edmund Campion or Robert Southwell, who would celebrate the sacraments and often teach members of the household, including girls, Latin, Greek and Scripture. It was easier, at times, for these priests to work collaboratively with women, whose movements were less spied upon than men’s. Many of these brave women would later become members of Mary Ward’s pioneering order.

Some of the men in these family networks schemed for the political restoration of a Catholic monarchy. The famous Gunpowder Plotter’s portrait in the National Portrait Gallery in London shows several relations of Mary Ward and her companions plotting energetically. While her uncles John and Christopher Wright and Thomas Percy died in the Gunpowder Plot, Mary and her friends dreamed of another kingdom altogether, and the earliest portrait of them shows them sitting together, planning their great venture. At this time there were only two choices for women in the church, aut maritus aut murus – either a husband or a cloister. After a failed attempt to become an enclosed nun, Mary worked in the underground Catholic networks in London and there found that God was calling her to another way of life unheard of in the church. In 1609 she led a group of young women to St. Omer, near Calais, to begin a consecrated life without enclosure, despite the fact that the Council of Trent had expressly ruled that all women religious, even those like the Ursulines who were not founded to be enclosed, should live the cloistered life.

In 1611, she was told in a vision to ‘Take the same of the Society’, and understood that her companions were to live as the Jesuits did, taking their Constitutions, calling themselves the Society of Jesus and modelling themselves on the mobility and missionary focus of the sons of St. Ignatius Loyola. Neither church nor society was ready for this. Trent permitted no relaxation of enclosure for women, and St. Ignatius had insisted that there were never to be female Jesuits. Although Mary Ward’s sister Barbara and several early companions are buried in the English College in Rome, and held in honour there, some of the secular clergy of her day were hostile to the Jesuits. They referred to the new congregation as ‘Jesuitesses’ or ‘Galloping Girls’, hating and fearing what they represented. There were whispers of arrogance and immorality, of women aspiring to priestly roles. Society at this time considered women incapable of doing good to themselves, let alone to others, and was not prepared for someone who taught her sisters that ‘there is no such difference between men and women, that women may not do great things’. When a priest told her that ‘he would not for a thousand worlds be a woman, because a woman could not apprehend God’, she bit back the retort she could have made ‘by the experience I have of the contrary’; instead regretting the ‘lack of experience’ that lay behind his judgement. A Jesuit remarked that, while the ‘English Ladies’ were remarkable for their fervour, ‘when all is done, they are but women’, and their new venture was therefore bound to fail. Mary refused to believe that women were so weak and useless, insisting instead that “Women in time to come will do much”.

In 1611, she was told in a vision to ‘Take the same of the Society’, and understood that her companions were to live as the Jesuits did, taking their Constitutions, calling themselves the Society of Jesus and modelling themselves on the mobility and missionary focus of the sons of St. Ignatius Loyola. Neither church nor society was ready for this. Trent permitted no relaxation of enclosure for women, and St. Ignatius had insisted that there were never to be female Jesuits. Although Mary Ward’s sister Barbara and several early companions are buried in the English College in Rome, and held in honour there, some of the secular clergy of her day were hostile to the Jesuits. They referred to the new congregation as ‘Jesuitesses’ or ‘Galloping Girls’, hating and fearing what they represented. There were whispers of arrogance and immorality, of women aspiring to priestly roles. Society at this time considered women incapable of doing good to themselves, let alone to others, and was not prepared for someone who taught her sisters that ‘there is no such difference between men and women, that women may not do great things’. When a priest told her that ‘he would not for a thousand worlds be a woman, because a woman could not apprehend God’, she bit back the retort she could have made ‘by the experience I have of the contrary’; instead regretting the ‘lack of experience’ that lay behind his judgement. A Jesuit remarked that, while the ‘English Ladies’ were remarkable for their fervour, ‘when all is done, they are but women’, and their new venture was therefore bound to fail. Mary refused to believe that women were so weak and useless, insisting instead that “Women in time to come will do much”.

The Jesuit John Gerard, famous for his escape from the Tower of London after prolonged torture, knew from personal experience the vital apostolic role that women could play in keeping the Catholic faith alive. Gerard lent Mary Ward his copy of the Jesuit Constitutions, from which she copied her own proposed rule, ‘that only excepted which God by diversity of sex hath prohibited’ – what was strictly reserved to priests, in other words. New companions flocked to her: communities and schools sprang up from London to Munich, from Prague to Perugia. In Rome it was said that Mary and her sisters did such successful work among the prostitutes that there would soon not be a brothel left open in the city. Europe at this time was racked by the Thirty Years War and outbreaks of plague. Ignoring these perils with true Yorkshire grit, Mary walked over the Alps to Rome, armed only with the Jesuit Constitutions and her conviction of women’s capacity to ‘do great things’, to present her plan to the Pope. But her many enemies had reached him first, and Pope Urban VIII issued a Bull of Suppression against Mary Ward’s new congregation. In language whose violence remains shocking today it condemned her refusal to accept the moral and intellectual fragility of women and her arrogance in attempting spiritual tasks unsuited to the weaker sex. She was imprisoned as a ‘heretic, rebel and schismatic’ in 1631, shortly before Galileo was condemned.

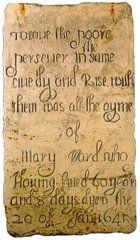

Mary returned to England with her work in ruins, only to find herself caught up in the English Civil War. She travelled north with three coachfuls of nuns and children, taking refuge first in Hutton Rudby, then in Heworth, where she died during the siege of York in 1645. There were difficulties at the time in finding a burial place for Catholics, but her sisters record that they found an Anglican priest ‘honest enough to be bribed’. Her tombstone in the Anglican church in Osbaldwick bears a coded reference to her determination that women might also take inspiration from St. Ignatius: ‘To love the poore, persever in the same, live, dy and rise with them was all the ayme of Mary Ward’.

Mary returned to England with her work in ruins, only to find herself caught up in the English Civil War. She travelled north with three coachfuls of nuns and children, taking refuge first in Hutton Rudby, then in Heworth, where she died during the siege of York in 1645. There were difficulties at the time in finding a burial place for Catholics, but her sisters record that they found an Anglican priest ‘honest enough to be bribed’. Her tombstone in the Anglican church in Osbaldwick bears a coded reference to her determination that women might also take inspiration from St. Ignatius: ‘To love the poore, persever in the same, live, dy and rise with them was all the ayme of Mary Ward’.

Her few remaining companions continued to live under her inspiration, and led by Sir Thomas Gascoigne, some began a secret community and school in Ripley which would eventually become the Bar Convent, York, founded in 1686 by Frances Bedingfield. Others worked in London, Paris and Munich. In London St. Claude de la Colombière met the sisters and exclaimed, ‘Oh! What holy women I have met here! If only I could tell you of their manner of life you would be astounded!’ Rome remained adamant, however, that Mary Ward’s founding vision should find no place in the church. Approval for a much-diluted form of the Jesuit Constitutions was only permitted years later on condition that the ‘English Ladies’ repudiated Mary Ward as foundress. The sisters were forbidden to display in public the famous Painted Life, a series of 50 paintings illustrating her life and spirituality, and were pressurised to destroy letters, portraits and documents referring to her. Various bishops would later permit foundations in their dioceses on condition that they had final jurisdiction over the general superior. This restriction caused a series of heated controversies until 1749, when Pope Benedict XIV made a landmark ruling in canonical history, for the first time opening up the possibility that women religious might enjoy the same apostolic mobility as men.

In the nineteenth century, meanwhile, Irishwoman Teresa Ball brought the inspiration of Mary Ward to Ireland, becoming the secondary founder of what became known popularly as the Loreto Sisters, who spread across the globe and retain the name Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Many generations of women in Manchester and Altrincham owe their Catholic education to the sisters. It took nearly three hundred years to gain final Papal approval of Mary Ward’s plan, but it was not until 2004 that the full Jesuit Constitutions could be adopted. When this happened, the original branch of Mary Ward’s sisters decided to adopt a name close to that envisaged by Mary Ward, who always insisted that they should live under the name of Jesus, becoming the Congregation of Jesus.

The Yorkshire of Mary Ward

Not everyone welcomed this change. Some past pupils and friends of the Mary Ward schools saw this as another step away from a fast-disappearing tradition. The Bar Convent in York had already ceased to be a grammar school and had become All Saints comprehensive school. The sisters had begun to run the famous convent as a museum and then as a bed and breakfast and conference centre, with a café and a shop. Was this new change one step too far? Some still question the implications of the sisters committing themselves to a rule whose structures reflect the male-oriented and hierarchical culture of the Tridentine era, when Mary Ward’s story embodies so much that Catholic women are still struggling with today.

But Sister Jane Livesey, provincial superior of the Congregation of Jesus in England, denies that the name change is about trying to recapture the past. ‘It’s about truth, about taking Mary Ward’s vision completely on board’, she believes. Mary Ward’s sense that holiness resides in ‘doing ordinary things well’ is typical of the Yorkshire approach to life, and a crucial part of her legacy. ‘We still have a long way to go before everyone shares her dream of a more inclusive church’, says Sister Jane. ‘But for us this is at least a step in the right direction’. Mary Ward’s cause for canonisation is well under way, and many of her admirers hope that it may take place during the pontificate of Pope Benedict XVI, himself a past pupil of Mary Ward’s sisters.

The past is certainly not the focus of Mary Ward’s sisters today. The Bar Convent in York is the oldest convent in Britain and featured in Channel 4’s documentary Convent Girls. The convent’s superior Sister Mary Walmsley, who also works in the All Saints school chaplaincy, welcomes visitors from all over the world, including Nuns on the Run star Robbie Coltrane, who featured the Bar Convent in his popular TV series B Road Britain. Sister Agatha Leach cares for the order’s sick and elderly sisters in the St. Joseph’s community in York, but is far from retired herself, spending so much energy and enthusiasm in promoting the Bar Convent and York in general that she was named ambassador for York in the 2008 Tourism Awards. Cheerful and vivacious and a brilliant communicator, Sister Agatha secured vital funding for the Bar Convent from millionaire Paul Getty after a chance meeting on a train. ‘I met a murderer on a train once, too’, she remarks, ‘but we’d best not go into that’.

Until her death in 2007 at the age of 95 Sister Gregory Kirkus, the Bar Convent archivist, welcomed scholars from all over the world who came to consult this priceless resource for people studying the role of women in the Catholic church. Now her successor, Sister Christina Kenworthy-Browne, continues the study of Mary Ward and has just published ‘A Briefe Relation’, the earliest biography of Yorkshire’s pioneer nun.

Next door, in St. Bede’s Pastoral Centre, Sister Cecilia Goodman welcomes visitors of all faiths and none who come for spiritual relaxation and replenishment. Run from 1987-1994 by a small group of Benedictine monks from Ampleforth, the centre now acts a place of support for the spiritual, psychological and emotional development of all who come, ‘but people are just as welcome who come just for a cuppa and some peace’, says Sister Cecilia. ‘Sometimes life demands a lot of us: those who are caring for others, for example, or feeling low, or just managing at work. We believe that creativity is the immune system of the mind, that it can help people to live more fruitfully. We offer anything from a cup of tea to creative activities and hand massage, from formal courses on meditation or Jewish-Christian relations to a simple chance to be heard. People offer what they can afford and find a breathing space here’.

Over in Hull Sisters Josie Bulger and Anna Hawke live and work in St Stephen’s Neighbourhood Centre, Greatfield. The centre is a community facility for local residents, which aims to ensure access to a variety of play, creative, leisure, and learning opportunities for all who come. Among the many projects on offer, the Girls Allowed Project was set up for young women aged between 12-16 years to help eliminate boredom and get them off the streets. Their activities range from Dance Workshops to Film-Making, Beauty Treatments and a training course on ‘how to be a good baby-sitter’. Thanks to working in partnership with Northern Theatre, the girls started to participate in regular dance sessions, learning new routines in all aspects of contemporary dance including cheerleading. Their commitment and willingness to practise cheerleading routines, resulted in their performing live as the Teen Angels during Hull FC matches at the KC Stadium, where they were treated like royalty and welcomed by everyone.

Over in Hull Sisters Josie Bulger and Anna Hawke live and work in St Stephen’s Neighbourhood Centre, Greatfield. The centre is a community facility for local residents, which aims to ensure access to a variety of play, creative, leisure, and learning opportunities for all who come. Among the many projects on offer, the Girls Allowed Project was set up for young women aged between 12-16 years to help eliminate boredom and get them off the streets. Their activities range from Dance Workshops to Film-Making, Beauty Treatments and a training course on ‘how to be a good baby-sitter’. Thanks to working in partnership with Northern Theatre, the girls started to participate in regular dance sessions, learning new routines in all aspects of contemporary dance including cheerleading. Their commitment and willingness to practise cheerleading routines, resulted in their performing live as the Teen Angels during Hull FC matches at the KC Stadium, where they were treated like royalty and welcomed by everyone.

Sisters by family ties as well as in religious life, Sisters Kitty and Sheila McManus cared for Bishop John Crowley during most of his years in Middlesbrough, creating with him a prayerful community at the heart of the diocese. Though both have now moved to London they carry in their hearts their many ‘Friends in the North’, made over the years.

It was the poverty of the Irish famine that drove many Irish families to the big cities of England in the nineteenth, living in crowded and squalid conditions. Canon Murray of St Wilfred’s parish, Hulme, Manchester believed that education was the way out of this crippling poverty and begged Mother Teresa Ball to send sisters from Ireland. Since they arrived in England in 1851 Sisters of the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary have been working for the rights and dignity of the poor, especially women. Conscious particularly of the challenges facing refugee individuals and families they teach them English and help them to settle. Sister Imelda Poole, who lived and worked in Middlesbrough diocese for a number of years, now lives in Albania, one of a number of Mary Ward’s sisters around the world who is involved in the issue of human trafficking.

Mary Ward’s family now extends across the globe in all continents. Over the centuries in schools and a wide variety of pastoral ministries her sisters have fulfilled her vision that ‘women in time to come will do much’. The position of girls and women in many parts of the world remains precarious – their job is by no means over. Currently the families of sisters in Orissa, India, have had to flee violent persecution and attempts to force them to abandon their faith. During the Soviet persecution of Christians in Eastern Europe sisters suffered imprisonment for their faith. Recently one of them, Sister Clara of Romania, returned to her prison. Sister Gemma Simmonds CJ, a lecturer in theology at Heythrop College, University of London, travelled to Ukraine to meet sisters of different congregations who had suffered imprisonment as Mary Ward suffered. ‘I was moved beyond words by the story of their courage and faithfulness after years of appalling treatment and brutal imprisonment’, she says, ‘it makes me all the more proud to be a follower of Mary Ward when I meet the likes of our sister Clara, who gave such extraordinary witness to her faith and her love of religious life’.

The days of persecution in England are thankfully over, and it is a particular joy to all Mary Ward’s sisters and their friends that the 400th Jubilee celebrations begin with a Mass in York Minster by the gracious invitation of Archbishop John Sentamu and their many friends in the Church of England. Sister Jane Livesey, provincial superior of the Congregation of Jesus says, ‘It speaks of a new spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. We are delighted to begin this celebration of one of Yorkshire’s great heroines together in the beautiful surroundings of York Minster’. Jubilee celebrations will take place all over the world throughout the next two years, but wherever they are, no one will forget that it all began in Yorkshire.

© Gemma Simmonds