‘Whatever house you go into let your first words be, ‘Peace to this house’.’ So, taking a leaf from the Bishop’s book, ‘Peace to you’. Sharing with you today coincides with an ordination jubilee year for me. To celebrate another Diocesan priest from a time of persecution is poignant. Nicholas Postgate lived in a hurting Church, and I think we do, too. The hurt which the Reformers did to Catholicism cannot be doubted. Within his hurting Church, Nicholas Postgate did an ordinary ministry in an extraordinary way. Whether we feel it or not, whether we recognise it or not, we are a damaged Church. In a few weeks time the successor of Peter, Benedict XVI, will come to our land. I wonder what Nicholas Postgate would have made of that. His allegiance to the Pope was fundamental to his priesthood. I think that is one key to any vocations crisis which we may feel in the hurting Church of the 21st Century. There are some other things, of course.

Jesus gave us the example of using very simple things, whilst bestowing upon them profound significance. He used water, bread, wine, a word and a touch. Our share in Christ’s priesthood is ultimately built on these plain things. Nicholas Postgate lived in a time of utter confusion, political turmoil, economic catastrophe. There’s not much difference between his world and ours. Let us not be mistaken: there are internal and external bruises which mark the body of Christ, the Church of today. They need healing.

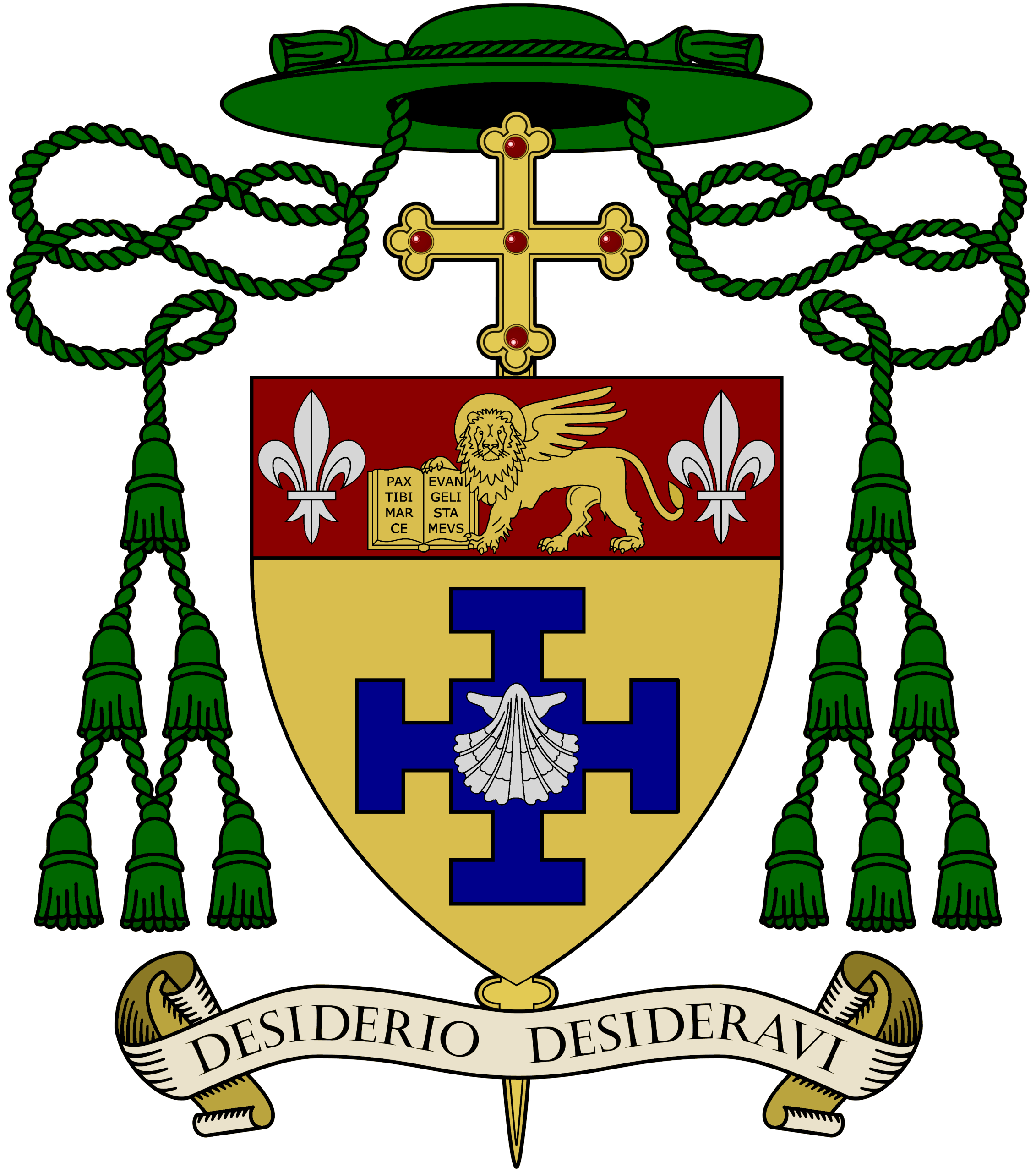

I come from East Yorkshire, associated with Bridlington and Beverley, though I have spent most of my 40 years as a priest in this end of the Diocese. Nicholas spent as much of his early ministry in East Yorkshire and Holderness as I have spent in North Yorkshire. My faith is built on the traditions laid down by Augustinians, and St John of Bridlington and St John of Beverley. Their charism, their gift to the church, was to plant cells of spirituality in the towns and hamlets which landlords entrusted to them. Back in the 12th century they helped bring into being a rudimentary parochial system in England. I delighted in accepting from Bishop John my appointment to be the parish priest of Guisborough, where there had been a truly wonderful pre-Reformation priory. In its shadowy ruins I could do some priestly work to continue the restoration of Catholicism to a town so cruelly and sadly deprived of its Catholic faith and traditions in the Reformation. Catholicism only returned to our town in the 1920s. From barely a dozen in 1927 when St Paulinus’ original church opened, our congregation is now over 300 souls.

Indeed today we celebrate Nicholas Postgate, a priest of our own district, Diocese, a martyr for that heritage of faith. Priests are diminishing in number all around us. Nicholas was ordained in 1630, the year King Charles II was born. His priesthood saw the union of England and Scotland in 1660. The devastating Civil War was barely a generation’s memory away. In many ways England was extremely volatile. The public economy was in a similar melt-down to our own, though of a different type. The beginnings of political union and nationalism were surfacing, whilst we are perhaps witnessing their gradual undoing. The slogan of a Protestant King for a Protestant people was being unfurled. A struggle for Catholicism was writ large in the midst of all this. We have a different kind of struggle to survive. I think the danger has always been to think that our survival will depend on an alliance with those who oppose Christ, whereas we should truly be an uncomfortable sign of contradiction, opposing falsity. Our culture is riddled with legalised opposition to Gospel and Christ-given values. This hurts the nation. This hurts the Church.

In Nicholas’ time there were for the whole of England perhaps a little more than the number of priests as we have in Yorkshire today. They mainly came from training in the English colleges abroad, and of course Nicholas had been trained in Douai, the forerunner of Ushaw, our last remaining Northern Seminary. Yet, somehow, the faith had survived persecution, the people were baptised, the Mass was celebrated, catechism was taught. More importantly, perhaps, prayers were said daily in Catholic homes. Of course political and social circumstances change, but the tasks of the priest have not changed. Now, at least Christians are talking and praying together. We celebrate what unites Christians instead of persistently scratching at the scabs and scars of division. The work of healing remains to be done. We priests should feel strong bonds tying us together, calling across the ages, asking us to respond in giving a quite simple priestly service to people. Today’s Gospel records Our Lord giving his pastoral instruction to his first disciples. ‘Whatever house you go into, let your first words be: ‘Peace to this house!” That is fairly straightforward. ‘Whenever you go into a town where they make you welcome, eat what is set before you.’ That is solid advice. Thanks be to the people of God, in my own priestly service they have never seen me go short. But bringing the healing of Christ through his word and sacraments is the powerful part of our priestly ministry. In the hurting and smarting world of his time, Nicholas Postgate struggled to do precisely that. He spent 37 years in East Yorkshire in the wooded wolds and the rolling vales just doing what we would consider ordinary things in an extraordinarily perilous situation. Unlike him, we do not have a price on our heads. We have the advantage.

Today’s Catholics are persecuted in subtle ways. We live in an acutely hurting Church and, so sadly, some of the deepest wounds are self-inflicted. In many ways our Church is deaf and deafened, for some it has been a struggle to hear the agonies of those most deeply wounded because their human dignity has been appallingly assaulted. The blessing of the ears after baptism needs to be repeated. The ‘Ephetheta’ needs to be repeated. ‘May the Lord open your ears to hear his Gospel, and your tongue to proclaim his praise’. I am reminded that Blessed Nicholas was captured baptising a baby at Ugglebarnby, not far from here. The healing work of priesthood still remains to be done. It is quite simple. Instead of priest-hurters, we need priest-healers; and priest-prayers, and priest-servants for our world. All the other priest-categories, priest-prophets, priest-preachers, priest-teachers, good and useful though they be, surely pale into insignificance. We often mislead young men into thinking that their gifts and talents are neither appropriate nor needed in the Church of today. Priesthood of itself is quite straightforward. We share a ministry of Christ which offers healing to the world. The simple vision is complicated by all sorts of human demands which cloud the urgent call of Christ: ‘Come, follow me’. Knowing the difference, and following the focus is at the heart of vocation.

Our faith is often sustained by very simple things. Thinking of priestly service, then, I want to share with you a reflection on three ordinary things. At first they will seem a little odd. A candle. A penny. And a bedspread.

So first of all, a candle. At the heart of Catholicism is the Mass. The Protestant Reformers of long ago knew from the outset that if the Mass was suppressed, then Catholics would be weakened to the point of extinction. That truth remains. If we are in any danger it is this. Take away our Mass and we have so much spiritual power drained away from us. However it is not persecution from enemies outside of the church we need to fear today, but disruption, interference, distraction from within. Our forebears – many of whom could neither read nor write nor count – measured time by the seasons and the festivals of the Church’s year. The feast days and the fast days were their calendar. The fast days were marked by penance and self-denial. But the feast days were marked by light, especially the light of a candle. The medieval Church had several festal days ñ usually in the quarters of the calendar – wherein the faithful were called together to bring candles to the church as testimony to their faith. This bringing of lights turned into processions of witness, full of symbolism: in towns like Guisborough where I live there were processions of light for all of Mary’s feasts in Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter, as well as the great festivals of the Lord at Christmas, Easter, Pentecost and Corpus Christi. The destruction of the great shrines in places like Guisborough Priory ñ namely the Burial Place of Christ for the Easter Triduum – and the Lady’s Light at the shrine of Our Lady, deprived the faithful of opportunities to give this witness to their faith. The suppression of pilgrimages and processions was an important part of the dismembering of the ordinary devout practices of the faithful. Not only was the Mass suppressed, but the opportunities to participate in devotion were taken away. With what wonderful foresight Fr Mercer restored Our Lady’s Light in the 1927 church at Guisborough, and it has incessantly burned ever since to this day. It is a simple piece of devotion.

So, what about the penny? On major festivals, when there were processions, not only did the faithful bring a candle to church, they also brought a penny. As they offered their candle to the priest, they also offered a penny, which was their church dues. This usually happened round about the Quarter Days, so each family in the parish offered at least four pence a year to the upkeep of the church. To us that does not seem much money. But it had to be carefully budgeted for by the head of the household, and charities or gilds were established to ensure that no one would be prevented from participating in the processions and offerings through embarrassment. Those gilds often expressed a particular aspect of charity or devotion: so there would be gilds associated with saints who were patrons of art or industry, or gilds of Our Lady or Gilds of the Blessed Sacrament. The economy of the local church was catered for within the framework of Christian love and practical charity. This framework of church life was obviously disrupted by the Reformation. The evolution of the modern state has its origins in fundamental changes to cultural practices originally founded on evangelical counsels. Welfare, a word which had medieval connotations of blessings attached to it, is now politicised and unchurched.

I mentioned the bedspread. In medieval times, the great processions obviously took place throughout the streets of the town, and the processional route was marked by bronze studs let into the roadway or footpath. These bronze studs were often decorated with the emblem of the local shrine. For example, at Guisborough the emblem of Our Lady was the Marigold, so at the floor of her chapel were marigold tiles, and we have incorporated them in the newly restored shrine in our new church. The processional route was marked out on feast days by people hanging out their bedspreads at the windows of their houses. Now the bedspread, or quilt, was a very important piece of household equipment. Not only did it afford warmth and snuggles in the winter, but it was also a symbol of value, wealth and prestige. When a person died, their bedspread was taken to the church to lay over their coffins during their Requiem Mass, and then again over their grave on the Month’s Mind, and again at their Anniversaries. It was customary for the prettiest bedspread to be draped over the Altar of Repose from Good Friday to Holy Saturday to mark the place where the Blessed Sacrament rested in the Easter Triduum. All these customs, which linked everyday life with the life of faith, crumbled away and were taken out of both the civic and the liturgical life of the people.

I mention these things because I believe that we have to capture and create devotions suited to our culture to sustain our faith in addition to the great act of worship at the Mass. This is something for the collective Catholic imagination to address. In an increasingly complex and sophisticated world, I am beginning to think it would be the use of relatively simple things, like a candle, a penny or a bedspread which may have a lasting effect in our minds and hearts. The ordinariness of a man like Nicholas Postgate may offer us some solutions to the vocations crisis of our times. Profoundly holding on to the unfathomable riches of his faith, he used quite simple things in his ministry.

We could begin again to measure our time against the Church’s calendar of fasts and feasts and festivals. We still have the use of the Quarter Days in our legal and academic calendars. We could make more use of devotional lights and candles in our churches and our homes. We could make more use of crucifixes, rosaries, pictures, shrines, ordinary artefacts dedicated to Our Lady, the Saints, or the mysteries of our faith. My mother had a huge wooden spoon in the kitchen which she christened Martha, which not only beat the eggs and the flour, but also the recalcitrant child on the knuckles when stealing the mixing bowl to scrape it clean. Little things given great dignity often help us with the ordinariness of our faith and help us contemplate the mysteries we celebrate and keep us but one step away from the Gospel. What a joy it can be for the priest to be offered a token of home-made unleavened bread, perhaps to use at the Eucharist or within a house-Mass. I really believe we are at the end of one era of Catholicism in England and stand on the brink of another. The waves of Catholic migration have stopped and slowed. Few, if any, Irish priests come to minister to the descendants of those who fled the famine in the 1840s. Indeed, we have all melted into a cosmopolitan, culture-tolerant, increasingly diverse but significantly vibrant Church with reduced numbers of nominal Catholics. The wider and more complex, unbelieving population of England is an open mission field. We are its missioners, for no one else will do it.

Simple faith can be profound. It truly draws its depth from friendship with God. He is not our enemy, he is our saviour. Belief is affected by everything that happens in life. Grace does not work in a vacuum. It is marked by soaring hope and searing disappointments. Faith is never completely fulfilled, because true faith always has magnetism and mystery. We want to know, we want to touch, we want to feel, we want to weigh and we want to measure. But the medieval candle, the penny and the bedspread remind us to live on the gift of grace; imagination invests these things with value, and faith allows them to be used for the greater glory of God. In this way life may be consecrated, just as the bread and wine we offer now ñ simple gifts ñ will become invested with a divine power. It is this which inspires a man like Nicholas Postgate to follow a calling to be a priest. Above all, we need healing priests, sensitive to mending, pouring the salve of salvation onto the raw wounds of our engagement with worldly things. Priests of the 21st century will need all the spiritual imagination they can muster to restore vigour to both the devotional and sacramental life of the people. It was imagination and necessity which inspired the priest Blessed Nicholas to be an artisan gardener, may a similar stroke of grace inspire the artisans of Century 21 to become priests. We may be looking for vocations in all the wrong places, and overlooking the obvious in our own back garden.

Very Rev Canon Michael Bayldon