Homily given at Canon Michael Bayldon’s Ruby Jubilee by Canon Michael Ryan

Congratulations on your new church. All the hard work and numerous meetings have come to fruition – well done. Congratulations to Michael and thanks for asking me to say these few words.

There is a song that Liam Clancy – of the Clancy Brothers – used to sing called ‘The Parting Glass’. It’s about a man who at the end of his days ‘weeps for all the songs he didn’t sing and the promises he didn’t keep’. It’s a song about that difficult mixture of regret and longing and a good measure of thanksgiving for promises fulfilled. Maybe there is something of that song in Michael’s heart this evening.

In a way, every life is about songs and promises, the songs we sing and those we don’t sing, the promises we keep and those we don’t keep. And out of the songs and the promises of our lives we quarry our own individual and unique existence in this world.

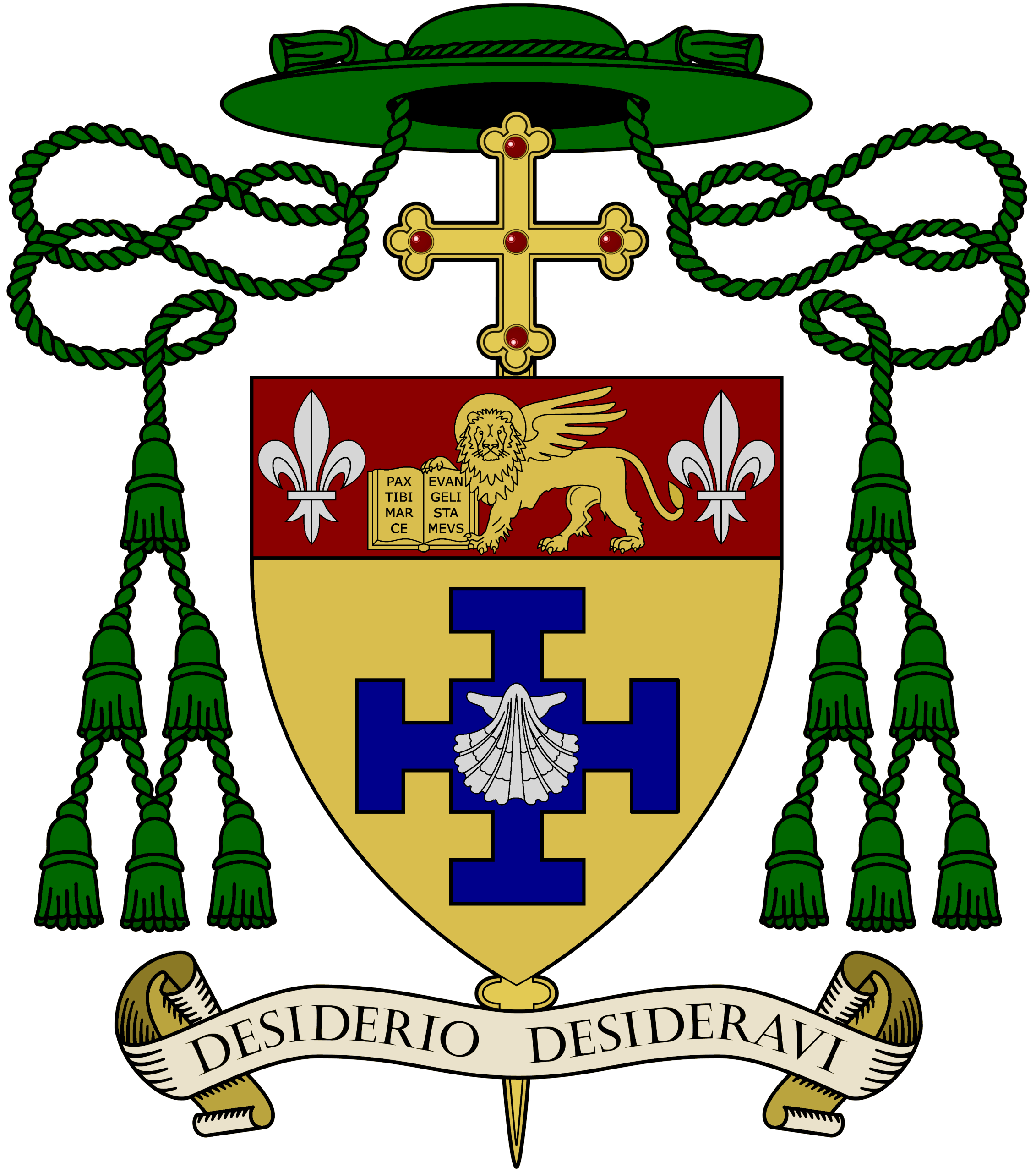

So, on marking 40 years of priesthood, Michael is thanking God for the songs and promises of the last 40 years, and he is looking forward with hope and confidence to the songs and promises of the years to come. And part of that marking is looking back to his ordination day in Beverley when Bishop John Gerard McClean laid hands on him – it is looking back to the people who gathered to celebrate that day with him – Agnes and Bill, his parents, and his friends including Joe O’Mahoney – I was MC on that special occasion – it is looking back to those ‘still to the good’ as we say, and to those who have died.

But he looks back too, not just to his ordination day 40 years ago, back not just to the faith communities that the parishes of Bridlington and Beverley were for him, back not just to the faith community that home and family were for him. He looks back too to his Baptism and his First Confession and his First Communion and his Confirmation. And important and all as these events were for him personally, he is looking back much further than that to understand what ordination or priesthood mean.

He is looking back tonight to the time when a man walked on the earth to show us what God was like and is like, and to help us understand qualities like truth and mercy and freedom and forgiveness and love; to help us understand what these meant and what they could mean for us and for our world.

That man we believe was God, and he brought together a very disparate group of people who continued his work on this earth. And his followers bonded themselves into a community, the community of God’s family, what we now call the Church. And out of that community, individuals were called and are called to minister as priests to God’s family.

That, if you like, is where the songs and the promises of Michael’s life come in. There was a call, a call that came to him as a young man. There was an answer and there is a priesthood. And for the last 40 years that priesthood has brought him to five different parishes and it was in those places that the songs and promises of priesthood found expression. Let me mention a few of these expressions – expressions of your priesthood outside your parish. I do not mean to embarrass him on this special night – I relate only what is factual.

He will probably remember inviting Fr Tom O’Connell and myself to his sitting room in St Peter’s, Scarborough in the early part of 1979. He proceeded to introduce us to a new Rite that had been approved by Pope Paul VI a few years earlier. That Rite was the RCIA – Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults. It was officially approved for use in this country in 1987. We had a draft copy of it in 1979! Whatever kind of presentation you gave us Michael, it seemed to make a huge impact on us both. At the ripe old age of 82, Tom is still running the RCIA in Scarborough and he has eight people coming into full communion with the Catholic Church this Easter. Since that day in St Peter’s Rectory when the seed was sown, I have been involved in the RCIA. It is possible that neither Tom nor myself would have caught the vision if you had not introduced us to it in those early years.

A change of scene, Fr Joe O’Hare of Stockton Diocese, California, once inquired of me ‘did I know a priest called M Bayldon?’ This Michael B had been commissioned to write a series of articles on ‘The Church and Ecumenism’ for a prestigious magazine in the United States. Fr Joe found the articles both challenging and inspiring and he sent them on to me. They say something, don’t they, about a prophet in his own country!

On the education scene, our debt to Michael is immense and must be recorded. While running a parish, he travelled the length and breadth of this Diocese sorting out problems in schools and colleges and giving help and support to teachers and governors. When the occasion demanded it, he was capable of giving a good kick in the posterior! Also he had to liaise with seven different education authorities in this Diocese. I do know of the high respect he was held in in the York authority. He also made a contribution at a national level.

All these were expressions of his priesthood – to quote St Peter: ‘you were called to be a shepherd of the flock that is entrusted to you, to watch over it, not simply as a duty, but gladly, as God wants, not for sordid money, but because you are eager to do it.’ Nobody could doubt Michael’s eagerness in carrying out all these duties.

Someone once said that priesthood, like religious life, is a sign of a melody beyond the ordinary song that we sing and it’s a promise beyond the ordinary commitment that we give. I’m not too sure about that because there is always the temptation to turn religion into piety, to turn priesthood into something so extraordinary and so holy that we forget that it’s ultimately an ordinary person living an ordinary life.

And those who struggle to live it are no better or no worse than others. Those who are priests are priests not because they just WANT to be but because, in some peculiar sense, they feel they HAVE to be. Because that call of priesthood, that call of inconvenience and unreason is just there for some people and not answering that call is almost not living at all.

Priesthood is about a lot of things that shape us and that we shape but at the end of the day, priesthood is about witness. Words are important, of course, and priests use a lot of them but words, as we say, can be cheap and people may choose to believe them or not, but no human word reaches the depths to which real witness goes.

This is one of the frightening things about priesthood, about actually being a priest. People look to Michael and to every other priest as if qualities and values – like truth and right living and holiness – come automatically, as if the frailties of the human condition are not applicable to us who happen to be priests. As if somehow we priests have some magic formula, some special grace that inoculates us against the limitations and failures of the rest of the human race.

Believe me, when Michael was ordained, when the Bishop anointed him with chrism and laid hands on him, it didn’t change his human nature one iota. He was the same three and two-pence as he was the day before.

But what was different was that he was given a responsibility and an authority to attend in witness and in service to those given to his care. What was different was that he was given and accepted a ministry of God’s presence in the world. And what this means in simple language is that it’s Michael’s work as a priest to help to open up the presence of God to people. As Pope John Paul said ‘priests are called to reveal the presence of Christ, embodying his way of life and making him visible in the midst of the flock entrusted to their care’.

And this isn’t something that is neat and packaged. This isn’t about having ‘ready answers’ or ‘neat solutions’ to the messiness of life. This is about ‘mystery’. This is ultimately about standing humbly before our God in wonder and awe, trying to grasp something of the whiff of God through our own experience and our own living, through what God is saying to us in the scriptures, through what God is saying to us in our own lives. This is about trying to plot a track for the kind of life God calls each one of us to live.

It is not about knowing all the answers. It’s not about knowing better than anyone else. It is about opening up, one hopes, delicately and respectfully, a window into God’s world.

That’s what priesthood is and Michael is thanking God for 40 years of service, for the songs that have been sung and for the promises that have been kept. And, like the singer of ‘The Parting Glass’, he will be aware too of the songs he didn’t sing and the promises he didn’t keep. That’s part of it too, part of the story of his life and of every life, the regrets that if we are honest are always just below the surface of the rest of our lives, the words he should have said and didn’t say, maybe too, the words he shouldn’t have said and did say, the times when failure or fear or sin limited and dulled the presence of God, rather than opening up the presence of God.

This may not be the worst of times for the Church and for the priesthood but it is certainly not the best of times either. When Michael was ordained 40 years ago, the bright promise of the Second Vatican Council was lifting hearts and minds, and morale among priests was very high. We had the wind on our backs. The Church and everything it stood for was granted at least a hearing on every platform of substance.

Now things are different: morale is low, fewer are going on for the priesthood, that great pedestal that priests were on when Michael was ordained is now in bits around our feet. And I’m happy that it is – because on a pedestal is absolutely the last place a priest should be.

And even though I obviously regret the great scandals that have rocked the Church in recent years, even though I obviously regret the terrible pain that has been visited on so many, and even though its painful to acknowledge the diminishment of priesthood that all that awfulness has brought with it, I sense too a new reality dawning for the Church and for priesthood.

I sense a new freshness, a new humility, a new respect based not on position or privilege or elitism of any kind but based on an acceptance of our vulnerable humanity in the face of life’s difficulties.

In years to come there will be other songs that we will need to sing and other promises we’ll need to keep. But maybe now we’ll do it with a bit more humanity and a bit more humility.

So Michael, as we give God thanks tonight for your 40 years of priesthood and assure you of our support, we encourage you to continue responding to the call of Jesus, continue with your brothers and sisters to be an Easter People, with ‘Alleluia’ as your song, and continue to respond to the question Jesus asked us all tonight: ‘Who do you say I am?’

Amen.

Canon Michael Ryan