A Talk by Lucy Beckett

It was with enormous pleasure that on Wednesday 21st October the Cleveland Newman Circle were able to welcome Lucy Beckett who shared something of her long-held fascination with Cardinal Pole. It was against the historical background of the English Royal Family and the Papacy of the early sixteenth century that she outlined the major influences on this interesting, yet nonetheless sad Englishman (who had been included in one of her novels The Time Before You Die: a Novel of the Reformation).

Reginald Cardinal Pole was born to Margaret (Countess of Salisbury) and Sir Richard Pole in 1500 but had a very much better claim to the throne of England, through his maternal grandfather George, Duke of Clarence, than did the Tudors. His father, a loyal Tudor courtier, was murdered merely for being a threat. However, Henry VIII did treat Margaret, best friend of Katharine of Aragon and later Governess to the Princess Mary, well; giving her cleverest, gentlest, most good looking and courteous son a fine education. First of all he was sent, at the age of seven, to the Charterhouse at Sheen (an alternative name for Richmond in London) where he imbibed the Carthusian way of life. By the age of 13, he had moved to Oxford where he remained for the next seven years. Here he was taught by humanist scholars who dedicatedly concentrated on the Classics; frequently teaching him from beautiful editions. Cut off from the world of politics, he began a studious, pious life civilised by books, libraries and gardens. Pole finally went abroad to complete his education at the University of Padua, also spending a great deal of time in Venice.

During the 1520s, a cloud descended upon England as Henry VIII became determined to have a son. Despite having been married to Katharine of Aragon for more than 20 years, he went through a mid-life crisis and fell in love with Anne Boleyn. He wanted to marry her for he thought that, given she was so beautiful, she would surely be able to give him a son. So, he began bullying Pope Clement VII and in 1530 asked Pole, now returned from Italy and living back at Sheen, to plead his cause for a divorce in Rome, offering to make him either Archbishop of York or Bishop of Winchester as a reward. Pole, more interested in the writings of Augustine and the Church Fathers, felt he was unworthy of such elevation; that he was too young, after all he was not even ordained and anyway Henry’s case was not a good one. Despite being brave enough to express his opinion, Henry completely lost his temper to such an extent that Pole thought he was going to kill him. He, therefore, rather reluctantly agreed to tour the Italian Universities taking learned opinion about the divorce. After numerous delays, he eventually left in 1532 but did not return again until 1554!

In the meantime, Henry’s behaviour went from bad to worse and in 1533 Thomas Cranmer dissolved his marriage to Katharine of Aragon. On 24th or 25th January 1533, Henry and Anne, who was by now pregnant, secretly married in the presence of a handful of witnesses. Cranmer, however, did not learn of the marriage until a fortnight later. In dumping the authority of the Pope, Henry allowed other Reformers in but very few at the time, with the exception of maybe Thomas More, John Fisher (the only Bishop in England to make a fuss) and about 18 Carthusian martyrs, grasped the scale of what he had done. Henry was no Protestant rather a superstitious Catholic whose mistake was to separate the English Church from the rest of the Church and make himself the Supreme Head of it. There was no change to The Mass, or other Sacraments, and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, an entirely separate issue, came later.

Six months on and Anne gave birth to the Princess Elizabeth; so Henry decided she was no more use to him. He had her tried for both adultery (of which she may have been guilty) and incest. In 1534, she had her head chopped off and 11 days later, Cranmer married Henry VIII to Jane Seymour. By 1536, Pole had completed and sent to Henry a long treatise attacking his claim of royal supremacy over the English church and strongly defending the Pope’s spiritual authority. This document was later published, without Pole’s consent, as Pro Ecclesiasticae Unitatis Defensione (In Defence of Ecclesiastical Unity). Nonetheless, Cranmer was so impressed with the intellectual quality of the arguments that he said no-one else must see this document and all we have today is an Italian copy. Under such circumstances, there was no way that Pole could return to England and so he remained in Italy.

Good, intelligent people in Rome realised that Reformers, such as Martin Luther who reputedly posted his Ninety-Five Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany on 31st October 1517, had been successful because the Church was in such a poor state. The big, corrupt Popes, Julius II and Leo X, were not good moral examples for they had too much money and allowed plenary indulgences to be sold in order to help re-build St Peter’s. Many Cardinals and several Popes had behaved badly until Paul III, a remarkably good Pope with patient, diplomatic skills, set a reform movement going in 1536 by commissioning a report, The Consilium de Emendanda Ecclesia, on the abuses in the Catholic Church.

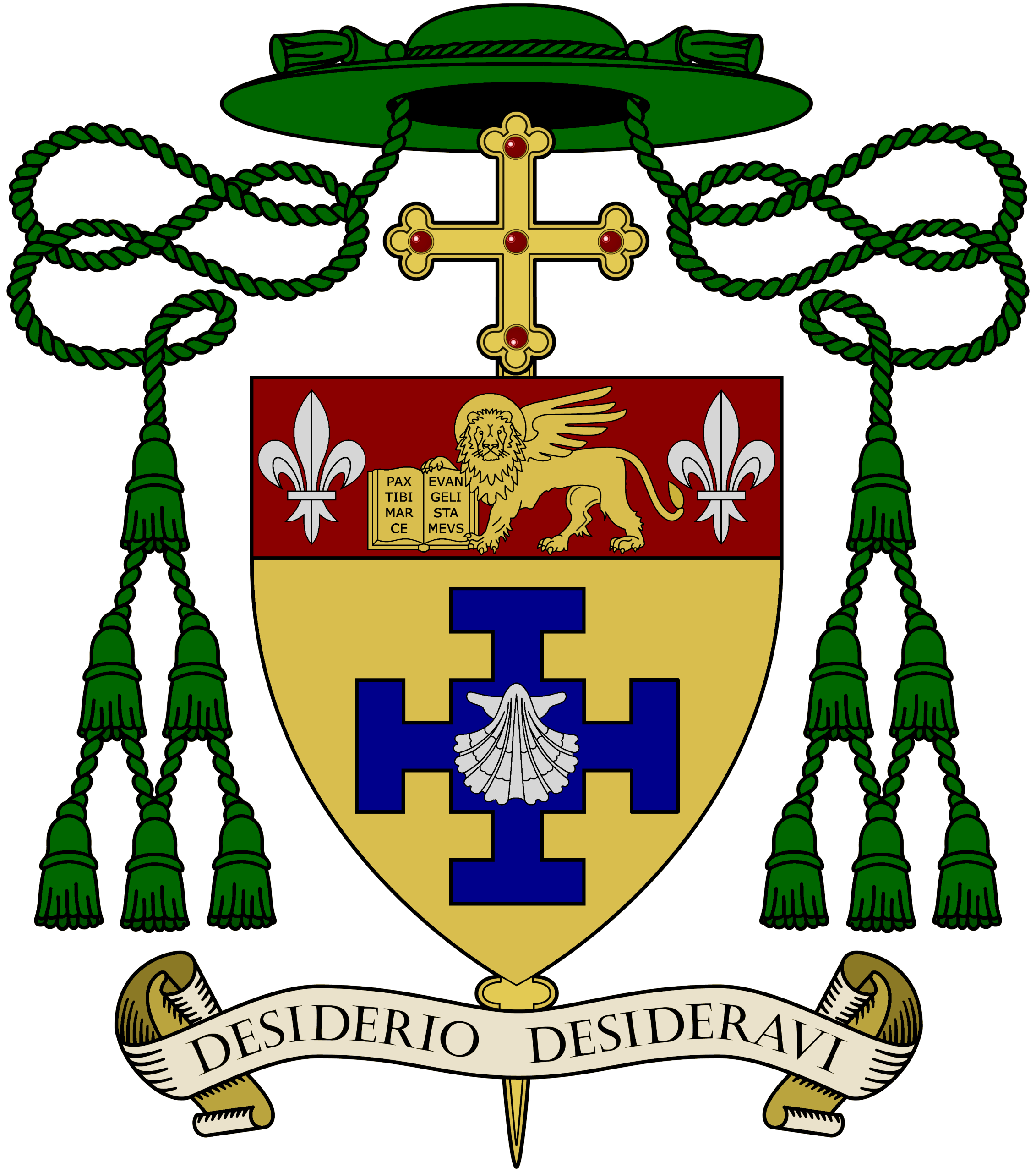

Pole was still a layman at this time, but it was thought that he should now take deacon’s orders and be made a cardinal. The prospect filled him with dismay, and he endeavoured to convince the Pope that it was at least untimely. It would not only destroy his influence in England, but involve his family in some danger. The Pope at first yielded to these representations; but others were so strongly in favour of his promotion that he returned to his original purpose. The papal chamberlain was despatched to inform Pole of the final resolution, along with a barber to shave his crown; and Pole eventually submitted. He was made a cardinal on 22nd December 1536, deriving his title from the church of St Mary in Cosmedin. Henry VIII was enraged by Pole’s Cardinalate status but forbore to show any open sign of anger. In the following February, Pole was also nominated papal legate to England.

With regard to the Consilium de Emendanda Ecclesia, Reginald Pole had been one of nine cardinals, and the only Englishman, appointed to review the abuses, which did not deal with theological matters but rather authority and behaviour. The commission was presided over by Gasparo Cardinal Contarini, a Venetian nobleman, 10 years older than Pole. Both men took their Faith seriously and were entirely loyal to the Papacy, pursuing their love of God alone. However, Pole theologically learnt from Contarini that not all that Luther had said was heretical. At the time, this was dynamite because few could hold that there may be some truth in both sides of the argument. One of those who opposed them was the austere, puritanical but not terribly bright Neapolitan Gian Pietro Carafa (later to be Pope Paul IV). Paul III himself, however, accepted the recommendations of the commission’s report but did not commit himself to any immediate changes. In fact, the Consilium de Emendanda Ecclesia was never actually put into effect in its entirety; although many of the proposed changes were implemented as part of later reforms.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, which still represents the largest legal transfer of property in English history since the Norman Conquest, took place in England, Wales and Ireland between 1536 and 1541. Our local uprising, The Pilgrimage of Grace, took place in 1536 when the people hoped that Pole would appear with an army and become King; but there was no way he could do that. However, between 1537 and 1539 Paul III sent Pole on two diplomatic missions to persuade Europe’s Catholic monarchs to ally against Henry VIII. Unfortunately, both endeavours were unsuccessful, and Henry, in revenge for Pole’s treasonous activities, executed both Pole’s brother, Henry Lord Montague, in 1538 and his mother in 1541. Aware of what was happening to his older brother and mother, Pole contemplated returning home and obeying the wishes of the King; but he did not, rather choosing to stay in Italy and bear the difficulties from afar. Henry VIII declared that Pole must be found and assassinated, placing 100,000 Gold Crowns on his head but Pole bravely just got on with the work he had to do.

In August 1541, Pole was appointed papal governor of the Patrimony of St Peter (the area around Rome). He took up residence at Viterbo and gathered around him a group of humanists. Following many delays, The Council of Trent finally convened in Trento between 13th December 1545 and 4th December 1563 in twenty-five sessions occurring over three periods of time. Cardinal Pole was the presiding legate who on opening the Council with his first speech met with stunned silence until Cardinal Del Monte jumped to his feet and began singing Sanctus Spiritus; to which the entire Council joined in. Upon the death of Paul III, a few years later in November 1549, Pole was favoured by many, including the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, to be the next Pope. In fact, he narrowly missed being elected by one single vote but the office eventually fell to a Frenchman, Julius III, only after the French and Italian prelates refused to endorse Pole’s candidacy. The Council of Trent and English Church History may have taken a very different route indeed if Pole had become Pope. Shortly after this Carafa, the fiercely anti-Protestant Cardinal began circulating propaganda against Pole himself and for the first time he met conflict within Rome. Some said that he was speaking virtually as a Protestant and others that he was a coward who was wrong throughout. Pole could do nothing but stick to his work and what he believed in.

By 1553, Edward VII had died and Mary Tudor became Queen. Julius III constituted Pole as legate to Queen Mary, the Holy Roman Emperor and to Henry II of France. His departure was delayed by one year because Charles V held that Mary should be married to his son Philip of Spain, in that way isolating France from England, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. The people (as had both their mothers) wanted Mary to marry Pole himself but Pole had no such aspirations. He wrote to the Emperor of the great importance of immediately reconciling England with Rome. However, the more worldly-minded Pope, Julius III, perceived that postponement was inevitable, and, in order to preserve Pole’s mission from an appearance of undignified inactivity, made over to him the unpromising task of endeavouring to make peace between the Emperor and Henry II as well.

Eventually Mary did marry Philip II in 1554 and although Pole sent Philip a letter of congratulations, really he believed that the Queen would have been better to remain unmarried. He himself arrived at Dover on 19th November 1554 riding onto Canterbury attended by a large company of noblemen and gentlemen. At first, his visit started very well; peacefully with three or four monasteries being re-founded. Proceedings against Cranmer were sent to Rome for judgment, where sentence of deprivation was pronounced against him and the administration of the See of Canterbury was committed to Pole on 11th December 1555. At the same time, Pole was raised from the dignity of cardinal deacon to that of cardinal priest, the day before he was ordained as Archbishop of Canterbury. Though he felt it a serious additional responsibility, he agreed to accept the primacy, on the understanding that he would not be compelled to go to Rome again.

Four years turned out to be insufficient time for Queen Mary and Cardinal Pole to restore the Old Faith and both died, coincidentally, on the same day, 17th November 1558. It may be that both might well have been heartbroken at the discredit thrown upon their zeal, and the hopelessness of the political outlook. Pole was buried in Canterbury Cathedral with a very plain headstone set in the wall above Thomas Beckett which read, but has now disappeared, Depositum Cardinalis Poli.

Reginald Pole had been a man of slender build, of middle stature, and of fair complexion, his beard and hair in youth being of a light brown colour. His eye was bright and cheerful, his countenance frank and open. Several good portraits of him exist, in all of which he appears in the vestments of a cardinal, with a biretta on his head. There is much gentleness of expression in all his likenesses. His habits were ascetic. He kept a sumptuous table, but was himself abstemious in diet, taking only two meals a day, probably to the detriment of his health. He slept little, and commonly rose before daybreak to study. Though careful not to let his expenditure exceed his income, he never accumulated wealth, but gave liberally; and his property after his death seems barely to have sufficed to cover a few legacies and expenses.

Much of what Pole was advocating on his return to England was put into effect in Europe 10 years later by men such as Charles Borromeo and Philip Neri. Ideas such as every diocese having their own seminary so that priests could be better educated; making sure that the clergy were properly housed and only undertook one living at a time and ensuring that Bishops undertook more responsibility. Seldom has any life been animated by a more single-minded purpose, but its aim was beyond the power of man to achieve. The ecclesiastical system which Henry VIII had shattered could not be restored in England. Royal supremacy thrust papal supremacy aside, even in France and Belgium; and when in England papal authority was restored for a time, it was restored by royal authority alone, and had to build upon foundations laid by royalty. Worst of all, the papacy, itself fighting a temporal battle with the princes of this world, disowned its too intrepid champion at the last. Maybe burning Cranmer was a catastrophic mistake, the consequence of which would be felt later on, but Pole was no cruel, bloody sort of Papist but rather a slow, hesitant, mild mannered gentleman, who made great efforts to try and bring his Protestant opponents around.