On Wednesday 24th February, the Cleveland Newman Circle were privileged to hear Fr Philip Gillespie, Vice President of Ushaw College, Durham, present an excellent exegesis on the history and development of The New Missal, which is expected to be in use throughout England and Wales for Advent 2011. He urged the attentive gathering to be unafraid of the change, for the Latin roots of the text will be unaffected, and it is only because we have become accustomed to the vernacular English over the past 45 years that we will notice the difference.

He began by explaining that this New Missal was in fact the third edition published in 2002; the first being promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1970 as the definitive text of the reformed liturgy of the Second Vatican Council. A second edition then followed in 1975 and Pope John Paul II issued a revised version of the Missale Romanum during the Jubilee Year 2000. The English translation of the revised Roman Missal has been completed, the Bishops of the United States approved the final sections of their text in November 2009 yet we are still awaiting final approval here in England and Wales. The Second Vatican Council had stated that it was useful to use vernacular language where it assisted the people in a better understanding of the mysteries that were being celebrated. Latin, unlike vernacular language, transmits ideas very curtly and succinctly. This translation, therefore, aims to take the vast riches of the original Latin text and faithfully translate that language into a useable and orthodox form for the people – ortho meaning straight and doxa praise. In that way, presenting the right way of praying which keeps us in communion with others – our Parish, our Diocese, our Country and the entire Catholic Church. In other words it is trying to emphasise that we belong to something bigger than ourselves. It hopes to maintain the integrity of what is being prayed in a form of words which can be prayed out loud.

The intention of the Missal, therefore, is to worship God with orthodoxy. So together, as a community, we give God worship, because he is worthy of Praise and Glory, and we do so in the right way. Each generation has to re-discover the riches passed onto us and re-interpret them. Here we are doing exactly the same thing; we are standing on the shoulders of giants, in order to grow in ourselves – to build us up and form us in The Faith. We are better doing this together because we are made to be a community; in the words of John Donne ‘no man is an island’.

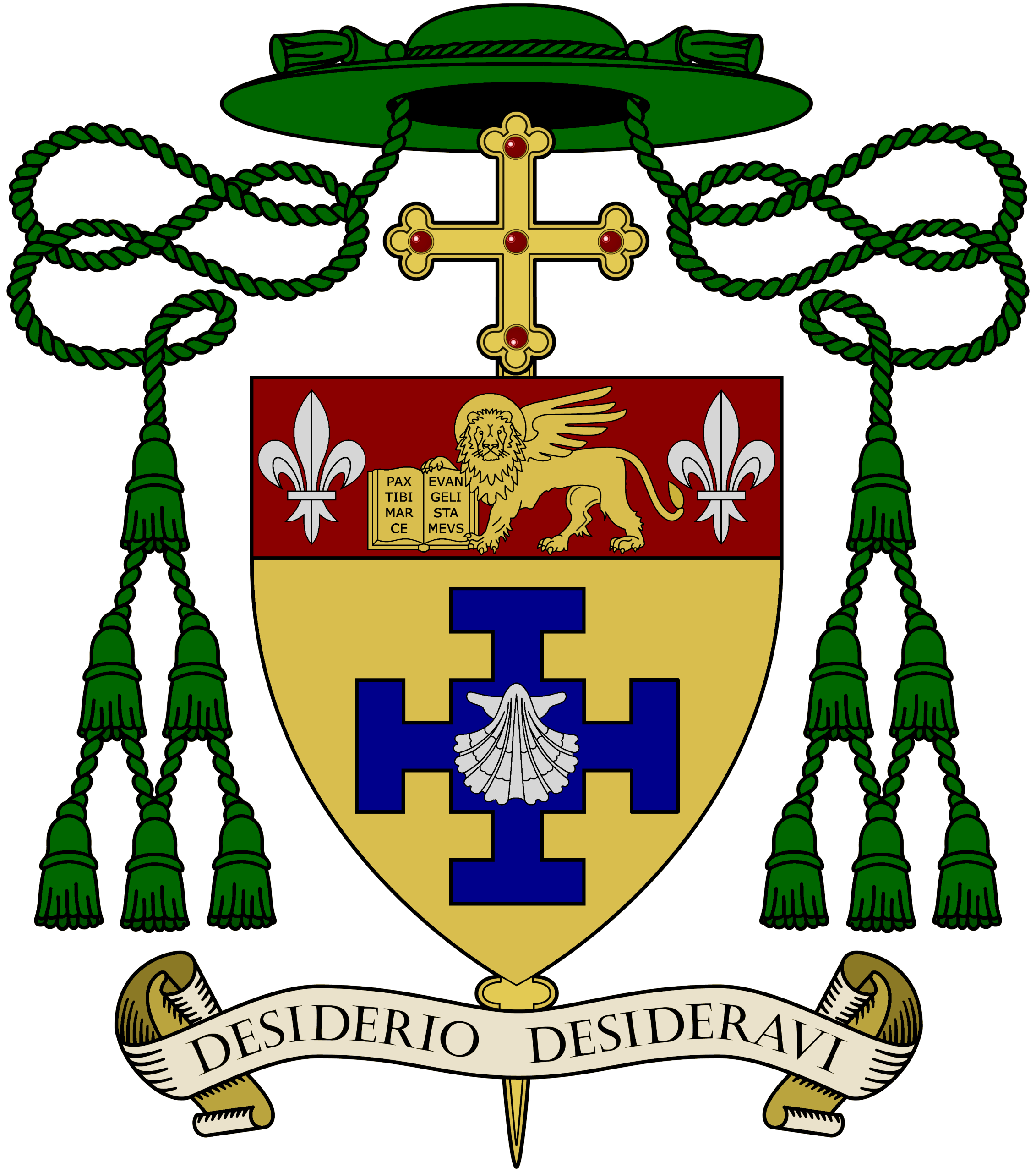

Fr Philip then went on to outline how the process had taken place. ICEL, or The International Commission on English in the Liturgy, which is a mixed commission of Catholic Bishops’ Conferences in countries where English is used in the celebration of the Sacred Liturgy according to the Roman Rite and has been in existence for about 40 years, was used. As was Vox Clara, which was set up on 20th April 2002. This Committee was established to advise the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments in fulfilling its responsibilities with regard to the English translations of liturgical texts. Its name means clear voice and with Cardinal Cormac Murphy O’Connor as one of its members, it was hoped that the completed translations would hold sufficient weight that they would be accepted in a straightforward manner. They are now awaiting the imprimatur, or seal of approval from Rome, that they are a worthy and good translation (and ready for use).

Three versions of this edition have been produced; all by different groups working in different parts of the English speaking world, which was no mean feat at all! All of the Bishops, in each of the English speaking countries of the world, had to look at the 2002 translation, criticise it, critique and send back their comments. It is not surprising, therefore, that this has taken eight years so far to achieve. Throughout this time, however, they have endeavoured to adhere to a principle of dynamic equivalence, which means that the text should literally be alive and get things going. It is not generally an end in itself but rather uses poetic licence in order to adhere to the Latin ordering. It is hoped that the translation is what it says on the tin.

It may be that we all prefer what we have grown used to for the past 45 years and will want to go back to it for a while, but really we should be asking ourselves what sort of language we should be using in the Liturgy, particularly when we gather together as a group. The new translation of the Missal does contain a different style of language but one that is still formally equivalent to the Latin and one where it is hoped that the good liturgical language will one day become so much part of us that it too will become second nature. It may make demands on us for a while, it may be a little poetic, but if it is read slowly, deliberately and reflectively then it is hoped that it will be inviting; inviting into a deeper, more fruitful relationship with God. We should see in the words a way, as outlined in Dei Verbum (1965), in which The Scriptures permeate our prayer or as the now popular practice of Lectio Divina encourages, a warm and lively love of the Scriptures. We should find ourselves enriched by the Church’s way of praying. It may require spade work to begin with but should ultimately prove better, more prayerful, more fruitful. Maybe the work which will be required in adapting to The New Missal will not be a bad thing in that it invites us into the Eucharistic celebration a bit more deeply.

It is recognised that Catechesis will be required during a period of transition but the changes are not earth shattering; they are not really even stilted, they are just different. In fact, much of the text is quite lovely. It respects repetition and builds God up to be most marvellous. We should, therefore, see this change as an opportunity; an opportunity to revisit The Mass, that we take to be so important, and, with joined hearts and minds, grow in its knowledge and understanding. We should allow ourselves to be nourished, using The Mass as food for the journey, so that we may carry on doing what we need to do during our time here on earth. The vision, therefore, of The New Missal is that we, the people, are all consecrated for worship; a worship which rightfully takes place in a Church building. It is now suggested that the Altar and Lectern be made of the same material because we are nourished at both the table of the Word and the table of the Eucharist. The Priest, with the help of the Holy Spirit, will offer gift and sacrifice while we, in our common priesthood, will offer our own lives. He, given in ordination, will preside over and lead a congregation in worship while the people will pray both for and with the Priest.

So far, The New Missal has been used successfully in some places although others report that it does still need some work; some patience, some stamina and some depth of vision. People may feel out of their comfort zone but must take the opportunity to use the poetic, semi-meditative reflectiveness to reach a deeper understanding of the meaning of The Mass. It is recognised that time, money and effort are needed to inform others of its true meaning and potential. This is not, as St Paul says, spiritual milk but rather the solid stuff; it will make us think. It was felt that a workbook, covering many of these issues and produced by the Bishops of England and Wales, which could be distributed around dioceses, would go a long way to allaying fears. Ultimately, however, Fr Philip felt that many of the concerns were more heat than light. With that, a very enjoyable and informative evening ended.