Father Tom O’Neill’s homily at Father Peter Keeling’s funeral at St Francis Church, Middlesbrough, on November 26 2024…

When Peter was in better health, he asked if I would speak at his funeral. My response was ‘Yes, on one condition that you speak at mine, if I go before you’. Peter has got away with it.

All of us could speak about Peter because he has left a part of himself in each one of us. I got to know Peter more than 50 years ago, in 1973. He was chaplain to the University of Hull and I was just down the road in St Vincent’s Parish, and I frequently called to the chaplaincy.

In 1973, you have got to get the context and the circumstances to understand the situation. Vatican II had just taken place in the previous decade. Changes were about to take place – or were they? That depends – from one person to another. That was the tension we lived with shortly after Vatican II. Some people were excited about the changes and others were anxious and afraid. This was dependent on individual temperament, nothing to do with knowledge or education. There were theologians, bishops and cardinals on both sides. So it is a great mystery, the Church, which we are caught up in.

Peter, being in the university and the university being what it is, was full of students. Students are hungry for knowledge and they wanted to know what all these changes in the Church were about.

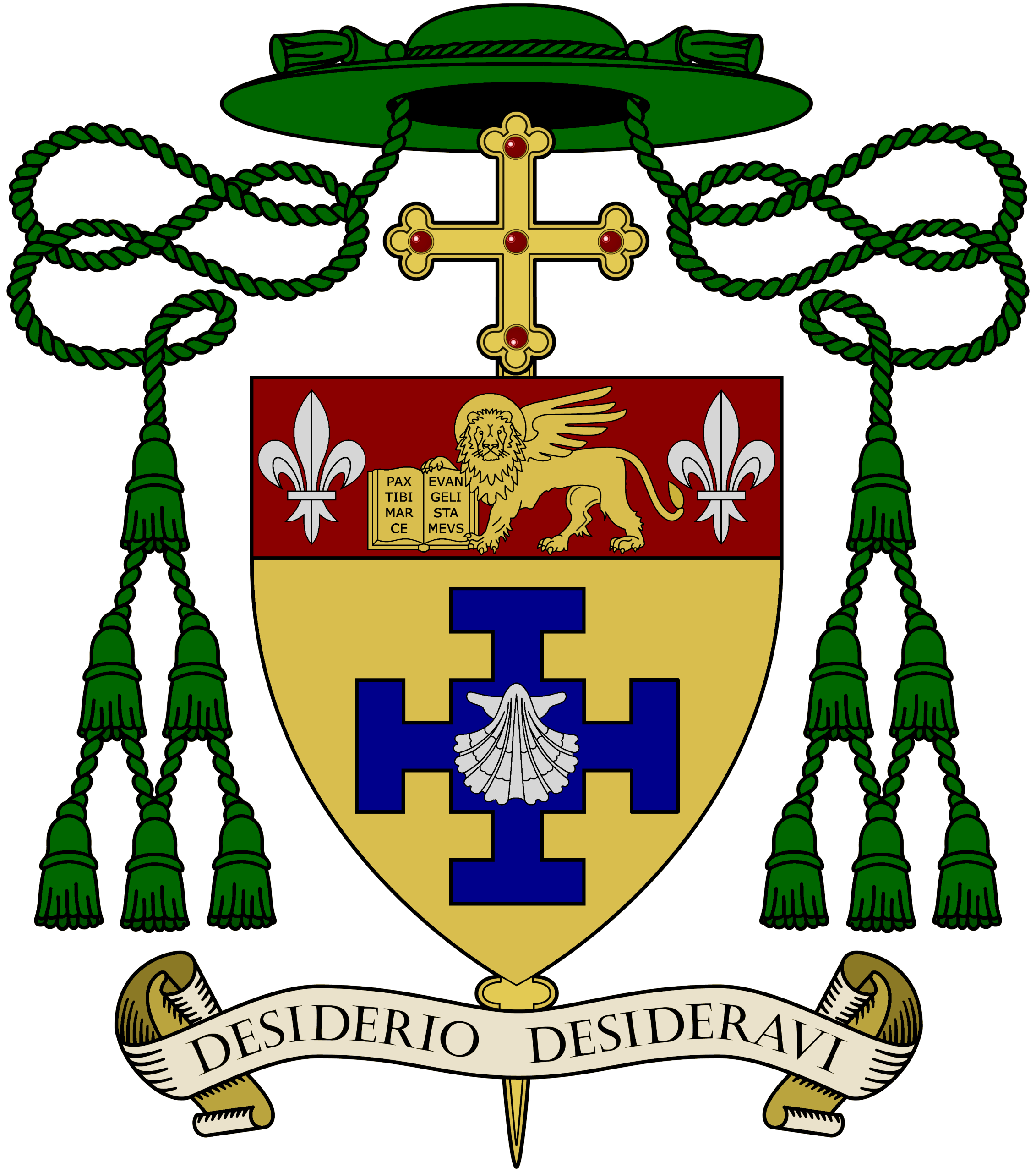

Bishop Terry anointing Father Peter Keeling in Lourdes

And so, Peter brought speakers to the university to speak and when they were of particular interest, he brought them also to speak to the clergy of the southern end of the diocese. These speakers were giants of the Church and I will name just three of them.

The first was Bernhard Haring, a German theologian, an advisor to the German bishops at the Vatican II Council. In turn, he spoke to the priests and emphasised that changes were taking place and not to confuse the changes with the reality.

He said: “Faith is faith; changes are a different thing.”

At that time, people were held back from the Sacraments because they had a broken marriage, or whatever, and he said: “Men for goodness sake, will you get out and look after the people of God and see that none goes hungry, or they will judge you at the last day and say, ‘I was hungry and you never gave me anything to eat’ – and don’t hide behind your bishops for answers” (excuse me, Bishop Terry!).

“All they can do is to give you the official line. Will you deal with each person who comes to you and see that they don’t go hungry and that they be nourished on the Eucharist."

The second speaker, would you believe it, was a canon lawyer. In fact, at the time, he was the leading canon lawyer of the world and was the advisor for the Vatican II.

He was called Father Ladislas Orsy, from Hungary. Strangely, he hardly spoke about canon law. What he did speak about was culture and the culture of different countries and different places. The culture is what holds the faith or, in the words of Jesus, the culture is the wineskins, the faith of what they carry.

And he simply said: “All the arguments are about wineskins; there is no argument about the faith. That remains. The wineskins must keep changing constantly in order to remain the same.”To put it simply, our difficulty is that we struggle to distinguish between the content and the container. If you take the date when you were born and the place where you were born, that has a profound impact on you – consciously or unconsciously. For example, people who were born in the 1940s and 1950s will think very differently from people who are born in the year 2000 and thereafter.

People born in the North of England will be thinking very differently from people in the South of England. Then he said: “Imagine, the difference between people in the South of Europe, like Italy, and people in the North of Europe, as we are here and Germany.” So, when we look at canon law, we interpret it very differently because of culture. So don’t mix up culture with canon law; this is what created arguments. Ladislas Orsy opened up windows of wonder to us in his interpretation of canon law.

A third speaker was Archbishop Anthony Bloom, a Russian Orthodox archbishop who lived in London, and an immense man of deep prayer.

His whole presentation to us, first of all was himself. You could see in his appearance how he was full of faith, full of Christ.

He would say: “Brothers, you must spend time with Christ if you are going to take anything of Christ to the people. It is not enough to say prayers and rattling off your breviaries. You have got to spend time with Christ. When you come to people, they will see Christ – and more importantly, you will see Christ in the people.”

That was Archbishop Anthony Bloom who has written a lot of little books on prayer (School for Prayer; Living Prayer).

These are just three speakers that Peter brought to us. And that man, in his prime, had such an influence on the south of the diocese, because of who he was.

Another thing about Peter, though I am only saying things that you know already, was Peter’s compassion. I saw that lived out in a real way when I was down at St Vincent’s, at the funeral of Joe Bradley, the gardener at the chaplaincy.

Joe Bradley did not belong to any church; he was just a good man. When he died, his funeral was in a little chapel in the northern cemetery in Hull. Peter was there because Joe was the gardener and I was there because Joe’s daughter worked in St Vincent’s Social Club.

The two of us were there in that little chapel. Peter started with the opening prayer and he got overcome and beckoned me to come and take over the prayers, which I did.

But what I saw in that moment on that day was the change in the family of Joe when Peter broke down. They changed; they just looked at each other. You could see there the most powerful sermon of all time.

The change I saw in Joe’s family was immense. They could see their father had such an impact on Peter, as he had on them. It taught me a lot about compassion – taught is the wrong word. I saw compassion. At that moment I saw Jesus weeping at the grave of Lazarus. I saw the effect. I am sure that every funeral which Peter led, those families will have experienced that same compassion and will have found shelter in that. That’s the kind of man he was.

That compassion reached out beyond the single person, beyond people. It reached out to the whole world. Peter had compassion on the world, on the planet, on the whole human race, and that is what took him with his fellow protesters down to the Ministry of Defence, chaining himself to the railings, protesting against the use of nuclear weapons.

He wanted to say we’ve got to stop this and look after our world and our people. That was his compassion. His fellow protesters paid their fine but Peter refused. So he went to gaol, rather than pay the fine. He spoke so highly of the prisoners, how they looked after him while he was in prison and the love that was in them and the charity that was in them.

In contrast with that, he used to joke with us, his so-called friends, saying: “Lads, I think might find a little road-stop or two, when you are trying to get into the Kingdom because you’ll have to pass me and I will say, I was in prison and you never visited me.”He was a big Justice and Peace man. That was so important for Peter. All came from his compassion, his care for the whole of creation. His God was a God of the Incarnation.

That is why Peter said to me after my agreeing to speak, he said: “Speak to them about the God I believed in. Don’t speak so much to them about me.”

So that when I am speaking about the God he believed in, there is Peter in that because he incarnated the God he believed in.

When you meet Peter, you meet hospitality. That is what you meet in Peter the man, Peter the person. The hospitality was the radical kind. By radical hospitality, I mean it was in his person that you met hospitality.

The first thing you experience when you first meet Peter is that there is a kind of quietness, a silence. You are not getting a gushing flow of his person at you. He is receiving you. He is receiving who you are; he is receiving the person in front of him. That is hospitality, the radical kind. Peter incarnated that.

So for him to understand and to speak of receiving Holy Communion is not something different from his life. It is something he is doing all the time, something we all do all the time. We receive one another – we receive Christ in the same way. That is the Peter we know. He never took himself seriously and he would laugh at himself, laugh at things that would happen to him and laugh at his own stories. While he took his God seriously, he never took Peter seriously.

Peter was a man who believed in the Incarnation. He knew that God became flesh in his flesh and he treated that Christ in him, as such. He lived with that Christ in him and you all experienced that Christ in Peter.

The only way you could say it is that there was a presence about him. There was something he had, and he had that something which all of us have. He had the Risen Christ going around in his flesh. We all have it. Peter had it and he knew he had it.

He knew everybody else had it and that is why when you meet him, he would look on you, as if he was looking at his God because that is what he was doing.

We are celebrating a great man and thanking God for the gift of him. He was the man for all seasons and I think it is very fitting that he was ordained in St Thomas More Church.

And he brought that God with him. We thank God for Peter and for the privilege of knowing him.